- Home

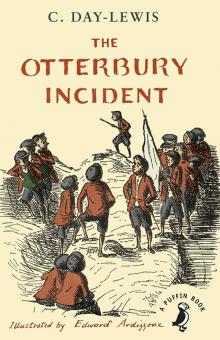

- C. Day Lewis

The Otterbury Incident Page 3

The Otterbury Incident Read online

Page 3

‘Just a minute,’ Toppy interrupted – he’s a tall, thin, whippy-looking chap, with a bit of hair always falling over his eye – ‘what’s this got to do with us? We didn’t break the window, did we?’

‘No, not actually, but –’

‘Well then. Yates doesn’t do our impositions for us, does he?’

‘He doesn’t offer to bend over when one of us is going to be beaten,’ Peter Butts chimed in.

‘That’s not the point,’ Ted answered. ‘What I mean is, we all kicked the football really.’

‘You’re crazy!’

‘The Reverend Edward Pijaw will now address the Sunday School!’ yelled Peter.

‘You shut up, Butts!’ I said, going up to him in a menacing way.

‘D’you want to be laid out?’

‘They’re windy!’ shouted the Prune. ‘Yellow Ted and his sissy gang!’

A general fight would have started that very moment if Toppy, to everyone’s surprise, hadn’t bawled out to his chaps, ‘Pipe down, all of you!’ Then he turned to Ted. ‘What d’you mean, we all kicked the football?’

‘Well, we were worked up; we tore into the school yard in a bunch, dribbling the football and passing it to each other. Then someone yelled “Shoot!” and Nick happened to have the ball then and so he shot. It might have been you, or me – any of us.’

‘That’s his bad luck,’ said Peter.

‘Yes, but look – if you shoot a goal in a soccer match, it’s scored to your side. And the same way –’

‘You couldn’t shoot a goal from ten feet away with the goalkeeper blindfolded,’ said the Prune.

It was this, really, that turned the tide: for Ted is centre-forward of the Junior School XI, and everyone knows he’s deadly when his shooting-boots are on.

‘Don’t be cheeky, Prune,’ said Toppy. He’d been looking rather abstracted, as he does when a bright idea is brewing up in him. He’s an odd sort of chap, Toppy. Behaves like a tough most of the time, and then suddenly for no apparent reason he’ll take quite a decent line. ‘You know, it could be rather wizard,’ he said, in a brooding sort of way – we were all gathered round him and Ted by now – ‘it could be rather wizard. These battles are getting stale anyway. Kid stuff. What a smack in the jaw for old Bellyache’ – that’s Mr Warner, our revered Headmaster – ‘if we turned up on Tuesday, the whole lot of us, with the money.’ He put on the Head’s voice – ‘What we must all strive for in this school, from myself down to the most junior boy, is the – ahem, ch’rrm – the corporate spirit. We must all be members of one big happy family. Muswell, you are not attending, take a hundred lines for gross insolence.’ Toppy flung the lock of hair back out of his eyes. ‘Yes, let’s give him a dose of his corporate spirit. We’ll form a Grand Alliance between your company and mine, Ted, and raise the money somehow. If any of you chaps doesn’t want to volunteer, let him take two places to the rear, and go and fry his face over a slow oven.’

Peter Butts looked a bit mutinous; but only the Prune broke ranks, edging slowly away and trying to look as if he’d lost interest in the whole business. I said we must sign a Peace before we could have a Grand Alliance. So I was instructed to draw up that pact. I did it on a sheet of paper torn from my diary, but later it was copied out fair, of course – on a big roll of parchment stuff we pinched from the Art Room, and we made real seals for it with ribbon and sealing-wax. Here it is, anyway – a jolly good historical document, though I say it as shouldn’t:

BY THESE PRESENTS

WE, Edward Marshall and William Toppingham, do declare a state of amity and alliance between our several armies, supporters and pursuivants, heretofore vulgarly known as Ted’s company and Toppy’s company, the said pact to be recognized hereinafter by the title of THE PEACE OF OTTERBURY, and to be binding upon the signatories and their supporters or pursuivants under pain of outlawry until such time as the pact or Grand Alliance aforesaid shall be declared null and void by mutual consent of the signatories or their accredited representatives.

Signed: William Toppingham

Edward Marshall.

While I was drawing up this document, I was vaguely aware of a feverish activity going on around me. In fact, when I brought it for Ted and Toppy to sign, they seemed a bit impatient – well, after all, a declaration of peace is an important thing, yet they just scrawled their signatures without even bothering to read it. They were sitting behind a counter they’d made out of an old plank resting on two dustbins, and the warriors of the late belligerent companies were filing past them, one by one, each man fumbling in his pocket and putting something on the counter. There were two heaps, one of money, the other of contributions in kind – penknives, Minicars, balls, pencils, bits of toffee – you know, all the sort of oddments you keep in your pocket. When everyone had contributed (I gave a tanner and a broken water-pistol myself), we had a pretty good collection of stuff, and 4s. 8½d. in cash. As for Nick, you never saw such a ‘Came-the-Dawn’ expression as he had on his face. And I must say it was strange to think how only twenty-four hours ago, on this very spot, we’d all been fighting to the death; and now here we were, weighing in with contributions to the Common Cause – young Wakeley even offered to give his white mouse, which was a pretty good show considering he and the mouse were absolutely inseparable – and Ted and Toppy sitting side by side as if they’d never laid crafty plans to annihilate each other’s armies.

Well, Ted was appointed treasurer, and it was agreed that Toppy and Charlie Muswell should take the toys, etc., in a satchel to the pawnbroker in West Street. As I say, there was a fair heap of them, some as good as new, and we thought they’d probably bring in quite enough money, together with the 4s. 8½ d. in cash, to pay for the window. Which just goes to show. What I mean, dear Reader, is – to anticipate my story – that you shouldn’t count your chickens before they’re hatched. And yet, if our contributions in kind had fetched the balance of the money we needed for Nick, we’d have had none of the adventures we did have, and this story would never have been written.

Toppy and Charlie at the pawnbroker’s

Presently, Toppy and Charlie returned, looking rather cast down. Toppy chucked half a crown on the plank.

‘That’s all he’d give.’

There was a general groan.

‘He only offered two bob at first,’ said Charlie Muswell. ‘Toppy bargained with him like anything. Honestly. Beat him up to half a crown. Pretended to walk out in disgust. And the pawnbroker chap rolled up his eyes and said he’d be ruined if he gave us more than two and threepence. So we started to put the things in the satchel again. And the pawnbroker said Toppy ought to be called Moses because he could get blood out of a stone. But he absolutely stuck at half a crown.’

Poor old Nick’s face had fallen like a barometer before a storm. But he took it very well; said how decent it was of us to have done our best, and not to trouble about it any more, and so on. But Toppy – his eyes were fairly glittering – said, ‘We’ve not started yet. We’re going to get this money if we swing for it!’

‘Stealing is barred,’ said Ted.

‘Who said anything about stealing? We’re going to raise the money. There’s twenty-four – no, Prune’s not interested – twenty-three of us. And if twenty-three able-bodied chaps can’t raise £4 odd, we might as well go and drown ourselves. Look, we’ve got till next Tuesday. We’ve Saturday and Sunday free anyway, and Monday’s the half-term whole holiday. Listen, you saps, we’ll hold Otterbury to ransom over the week-end.’

‘D’you mean a sort of flag day?’ someone asked.

‘There isn’t time to make the flags,’ Ted put in. ‘Besides, you’ve got to get permission from the police for a flag day.’

‘And people won’t buy flags except from pretty girls, everyone knows that,’ said Peter.

‘Flag day my foot,’ said Toppy. He struck an attitude on top of the rubble heap where he was standing. ‘The country is suffering from a shortage of labour. OK. We’ll supply it. We�

�ll offer to clean people’s windows, weed their gardens, do odd jobs – see what I mean?’

One or two boys groaned. Someone said, ‘But you’ve got to have ladders and sponges and stuff to clean windows.’

‘We can borrow them, can’t we, my poor fish?’

‘I don’t know how to weed. I don’t know a weed from a flower,’ said Charles Muswell.

‘You’re a drone, you dear little choir-boy,’ said Peter Butts. ‘A droning little Abbey drone.’

Ted snapped his fingers excitedly. ‘Carol-singing! Charlie can sing.’

‘Me sing in the streets? Come off it, Ted!’

‘Not by yourself, fool. Hands up who else of us is in the Abbey choir.’

Three hands were raised.

‘There you are, then. The four of you can practise. Get some other chaps from the choir to join you, if you like. Practise: then go round the town singing, on Saturday.’

‘But we can’t sing Christmas carols in the middle of June.’

‘Well, sing something else. Hymns. Comic songs. Anything.’

‘That’s just what I meant,’ said Toppy excitedly. ‘Everyone should do whatever he’s good at. For instance, Dick Cozzens is a slang expert – RAF slang particularly, because his brother’s in it. Why shouldn’t he offer to give chaps in the school lessons in slang? Twopence a lesson, say?’

The idea caught on now like a prairie fire. Everyone began talking at once, saying what they could do, making suggestions. It’s extraordinary, when you come to think of it, how, once one person has started a thing, the rest follow him as if they’d been madly keen on it all along. Like sheep going through a gap. Or like a trickling river that becomes a flood and sweeps every obstacle out of its way.

For instance, one or two chaps had the bright notion of borrowing brushes and polish from home and setting up a shoe-shine stand at the traffic-light cross-road in West Street. Then someone pointed out that the weather was set fine, and people only wanted their shoes cleaned when it was muddy. So this bright notion seemed to have had it. But Toppy, who’d been looking thoughtful, suddenly burst out with, ‘We’ve got to make their shoes muddy, then.’ And various ideas were put forward for this, and boiled down to the most practical one; and this idea was worked out in detail – you know, like Boffins working away in a back room to make some invention absolutely foolproof. And the final touch was a brainwave from Peter Butts which – but I won’t tell you yet how the idea was worked out, because it would spoil my next chapter. Read on, and you’ll see.

So there we were, everything going smoothly, everyone getting more and more enthusiastic. Except the Prune; and even he couldn’t tear himself away at first; he stood about on the edge of the crowd, trying to look as if he was above all this sort of thing. But public opinion was dead against him, and presently he did drift off.

The only real difference of opinion we had was about girls. It became obvious that some of the things we were planning needed girls to help, and some boys who had sisters about their own age wanted to bring them in on it. Others – specially Peter Butts – were frankly sceptical about this. He said that, once you let women into a thing, they always wanted to boss it; and anyway, Ted’s and Toppy’s companies had always barred girls. But Ted pointed out that the companies had now been disbanded, and were regrouped into one big organization – at any rate, for the purpose of Operation Glazier, which is the name we’d decided on for the week-end job (it was I who thought up this name, actually, a glazier being a man who puts the glass in windows) – so there couldn’t be anything in the rules against enlisting a few girls. We had a vote on it, and it was decided by seventeen votes to six that a limited number of females, approved by the committee, should be asked to join. The committee, also elected by vote, consisted of Ted, Toppy, Peter Butts, and myself.

Another question which arose was whether we should tell our parents about Operation Glazier, or bring in one of the masters – say Mr Richards. We were pretty well unanimous against telling parents, the chief reasons being that (a) grown-ups are apt to make a fuss about any activity, however harmless, which is off the beaten track, (b) Operation Glazier would lose the tactical element of surprise if half the town knew about it before it started, and (c) it would be much more fun to do the whole thing off our own bat. It was agreed, however, that if anything went badly wrong, the committee should be empowered to call in Mr Richards as an adviser.

Well, there we were, all the preliminaries settled and the plans laid. And it’ll show you how the scheme had caught on when I tell you that several boys who were supposed to go home for lunch (most of us bring packed lunches to school) didn’t get home till lunch was nearly over.

As the committee was strolling back to school, the Prune appeared again. He had a wooden box under his arm. It was a new box, about 1½ × 1 feet, with a lock and key. He said we could borrow this box to keep the money in. We asked him if this meant he’d changed his mind and wanted to be enrolled, and he said yes. I thought it was a bit odd. But the box would be useful, and we couldn’t very well refuse the Prune’s offer. So the box was handed over to Ted, as our treasurer.

And if Ted had been able to see into the future at that moment, he would have taken the box and filled it with stones and dropped it into the deepest pool of the River Biddle – yes, my word! – Ted wouldn’t have touched that box with a barge-pole. But, not being a crystal-gazer or a prophet, Ted put it under his arm, and we walked on.

4. Operation Glazier

The morning of Saturday, June the 14th, dawned bright and fair. This is not just a piece of novelist’s padding: it is scientifically accurate – I know, because I was so excited that I awoke early. The birds were kicking up a fearful shindy in our garden (it is called ‘the dawn chorus’); I got up and looked out of the window. The sun was just rising. Otterbury lay asleep, with that hazy look which promises a fine day to come, oblivious of the great events soon to disturb its ancient calm. The Abbey tower rode the morning mists like a galleon’s poop. Zero hour for Operation Glazier was ten o’clock, when the housewives of Otterbury would have begun their shopping.

For this chapter I shall use historian’s licence. A historian can’t be everywhere even when he’s writing about contemporary events. He pieces together documents, eye-witness reports, etc., and makes a coherent narrative from them. One advantage I have over the ordinary historian is that I don’t have to bother about a lot of dates, which are sickening things, to my mind, and quite unnecessary. It all happened over the week-end. First, a great victory; then the moment when disaster stared us in the face; then the recovery from this crippling blow and the turning of the tables on a dastardly enemy: looking back on it now from the historian’s viewpoint, I can see how events were divided into these three phases. As I say, I didn’t actually witness all the happenings related in this chapter, but I shall write as if I had been present at every point of the battle. So here goes …

At ten o’clock on the dot, a vehicle rumbled out of Abbey Lane into West Street. You would hardly have recognized in it the tank which, a few days before, had run the gauntlet at the Incident. A ladder was laid along its superstructure: instead of the gun, a long-handled mop protruded from the front turret; and on its sides, in large white letters, was printed:

KWICK-KLEEN CO.

THE RELIABLE WINDOW-CLEANERS

Why have a gloomy view of things? We will brighten them up for you at the cost of only 6d. per window. Just try us!

The vehicle passed slowly along the whole length of West Street, and then back again, the buckets inside merrily rattling. Two boys were pushing it, and a girl was pedalling. Every now and then they stopped, and the girl stood up inside the vehicle and looked around. She was Charlie Muswell’s sister. She’s supposed to be pretty; and it was Toppy’s idea that the window-cleaning party should have a bit of sex appeal. After showing themselves off to the morning shoppers, they moved away to the residential part of the town. They chose a house whose windows looked dirty, and rang the

bell. Of course they got a raspberry sometimes. And sometimes some fearful hag appeared at the door and drivelled over them – ‘Dear little children! What a lovely game you’re having’ – that sort of thing. Which was pretty riling, as you can imagine. But they stuck to it, and got several jobs, particularly when some of the early-morning shoppers, who had seen them in West Street, returned home …

At ten o’clock on the dot, the music started up. Charlie Muswell had got together a jolly good choir, eight of them in all, including three chaps’ sisters. They started outside the railway station, to catch people who were taking the 10.25 express to London; and they sang ‘Casey Jones’, which is a song about a terrible railway accident that took place in America, for the benefit of these passengers. They were pretty nervous at first, and I don’t blame them: after all, singing in the Abbey is one thing – people can’t very well boo you there; but singing in public, in the street – well, it takes a bit of nerve, you must admit. However, they’d practised really hard in the evenings, and one of the girls was wizard on the banjo, and a boy played the drum to keep them in time; and though I’m not musical myself, I thought they sounded super. The concert party moved from one place to another in the town, generally singing only one song each time. This was partly to avoid trouble with the police. It was amazing the way a crowd collected wherever they sang: it might easily have caused an obstruction if they’d stayed long anywhere. Things didn’t go quite smoothly for this party either. One or two young oafs started following them around, bawling out ‘What’s it in aid of?’ and other opprobrious remarks. Of course, Charlie Muswell and his boys could easily have laid them out, but if there had been a breach of the peace, the concert party might have had to pack up. However, the trouble was got over finally when Johnny Sharp turned up with the Wart, and warned the oafs off. Which shows that it’s an ill wind which blows nobody any good …

The Otterbury Incident

The Otterbury Incident